More Evidence That Serving Low-Income Frail Elderly Is Bad Business. Congress, and the CMS, have near-universal authority to manage Medicare. The ACA, MACRA/MIPS, and the IMPACT Act, are all intended to improve access, quality, and affordability of care for Medicare Beneficiaries. The frail, low wealth, elderly constitute the majority of Medicare’s most costly participants.

We are all searching for tools that help measure healthcare value. The Nursing Home 5-Star Rating program, 30-day Hospital Readmission Rates, and now VBP and MIPS for physicians

An LTCManagement Blog from November, 2014 described NIH sponsored research, which contended that a majority of the variation in SNF 30-Day rehospitalization rates could be correlated with variations in payor mix and patient demographics. Today’s blog cites additional evidence that well-meaning provisions in most of these laws, regulations, and policy decisions, are combining in ways that deliver outcomes that are completely opposite of those desired. Let’s examine the evidence which applies to medical practices.

MACRA/MIPS

If you combine recent DHHS and NIH funded research studies, CMS Value Based Purchasing (VBP) reports, and the current MACRA/MIPS program, I think you’ll realize the practitioners and providers who deliver primary, and personal care to the dual-eligible population are going to be punished by CMS for their efforts.

- Practitioners delivering Long-term/Post-Acute Medical care only have three paths to avoid the inevitable penalties. They can; join an Advanced APM, minimize their care for the frail elderly, or achieve an above average score under MIPS.

- Currently, there are NO Advanced APMs available for the LTPAC Population. Consequently that option to avoid MIPS participation is closed.

- By definition, the frail elderly are covered by Medicare – so there in no option to avoid MIPS by having below $30,000 of Part B payments, or seeing fewer than 100 beneficiaries.

- The only remaining option is MIPS participation. For 2017, avoiding MIPS penalties is simple – reporting any activity meets the minimum participation requirements. In the following years, current regulations specify that 50% of participants will be ‘winners’ and the other 50% will be ‘losers’. How will primary care medical groups that serve the low income, frail elderly fare in this cut-throat arena?

Here’s what we know from analyzing previous CMS data about LTPAC Medical Groups:

The CMS began sending larger medical groups QRUR reports back in the fall of 2013. Those reports told us that CMS considered LTPAC Practices “bad physicians” – we were ‘High Cost’. The message – correct your evil ways, or suffer future consequences. My old medical group, immediately after receiving our first QRUR report, began networking with our colleagues. The findings – 100% of a dozen medical groups we surveyed were designated high cost under VBP.

Statistical note – the LTPAC medical groups we collaborated with uniformly met the test for being Medicaid Providers under the EHR Meaningful Use Program – that meant each group had >30% of their patient encounters with individual patients covered by Medicaid. Typically, nearly 100% of our LTC patients exhausted their savings and qualified for Medicaid during their stay. This means they had Dual Enrollment (i.e. Medicare and Medicaid coverage).

The high cost status of all the LTPAC medical groups persisted ‘after risk adjustment’. All of the groups we surveyed had attributed patient populations which also met the test for being High-complexity (High complexity is defined as the top quartile of HCC risk scores for all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries nationwide. HCC=Hierarchical Condition Categories.)

Caring for low income older adults with high medical complexity is bad for business.

That brings us to the first study, a Report to Congress performed by the DHHS Office for Planning and Evaluation – Social Risk Factors and Performance Under Medicare’s Value-Based Purchasing Programs. The December 2016 report was mandated by the IMPACT Act legislation. It deserves careful reading, but here are the essential findings for this initial study:

III. Findings

- FINDING 1: Beneficiaries with social risk factors had worse outcomes on many quality measures, regardless of the providers they saw, and dual enrollment status was the most powerful predictor of poor outcomes.

- FINDING 2: Providers that disproportionately served beneficiaries with social risk factors tended to have worse performance on quality measures, even after accounting for their beneficiary mix. Under all five value-based purchasing programs in which penalties are currently assessed, these providers experienced somewhat higher penalties than did providers serving fewer beneficiaries with social risk factors.

- Conclusions

Social factors are powerful determinants of health. In Medicare, beneficiaries with social risk factors have worse outcomes on many quality measures, including measures of processes of care, intermediate outcomes, outcomes, safety, and patient/consumer experience, as well as higher costs and resource use. Beneficiaries with social risk factors may have poorer outcomes due to higher levels of medical risk, worse living environments, greater challenges in adherence and lifestyle, and/or bias or discrimination. Providers serving these beneficiaries may have poorer performance due to fewer resources, more challenging clinical workloads, lower levels of community support, or worse quality.

The scope, reach, and financial risk associated with value-based and alternative payment models continue to widen. There are three key strategies that should be considered as Medicare aims to administer fair, balanced programs that promote quality and value, provide incentives to reduce disparities, and avoid inappropriately penalizing providers that serve beneficiaries with social risk factors. Measuring and reporting quality for beneficiaries with social risk factors, setting high, fair quality standards for all beneficiaries, and the provision of targeted rewards and supports for better outcomes for beneficiaries with social risk factors, may help ensure that all Medicare beneficiaries can achieve the best health outcomes possible.

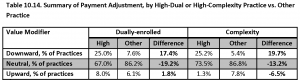

This study examined payment adjustments for all classes of providers serving Medicare Beneficiaries; Medical Professionals, Advantage Plans, Hospitals, Dialysis Centers, SNFs, etc. Its goal was to determine if organizations with either high levels of dual-enrollment or high-complexity[i] had differences in measured performance under the CMS’ various pay for performance (P4P) programs. If statistically significant problems appeared, the study then proposed possible solutions for the corresponding program. This table (from page 281) which examines large medical practices’ performance in CY 2015 is instructive:

What this table illustrates is that medical groups treating patient populations high in dual eligible, or high complexity beneficiaries had significantly lower value based performance than groups with ‘average’ Medicare populations. Unfortunately, the report didn’t take the next logical step – making the same measurement for groups with high levels of both populations (as is always the case for LTPAC medical groups).

The report restricted its examination to medical groups with 100+ members, the threshold for payment adjustments applied during CY 2015. Groups of that size are typically multi-specialty and associated with large health systems. While this study selected the 100+ group Size as their cut-off for analysis, all groups of two or more received VBP scoring in 2015.

- I believe that studying the larger universe of medical groups with two or more members will reveal significantly greater performance variations; there is some prerequisite amount of management skill that is required to reach that threshold of 100+ staff. Many small groups have lower levels of sophistication, fewer resources, and are more likely to serve populations with statistically significant variations from the norm. Again, as we reported many times, 100% of LTPAC medical groups were classified as High Cost under this value modifier algorithm; most had unfavorable ‘cost’ variations which exceeded two Standard Deviations above the mean.

This DHHS report should be on everyone’s reading list – it acknowledges a problem exists, but also assumes that there is an element of (voluntary) systemic difference in provider organizations. It reminds me of the debate about the low performance of inner-city students and their public-school systems. There are significant parallels: students/patients, teachers/practitioners, and schools/(facilities or practices). In both systems, it is difficult for the service recipients and organizations to relocate. However, in public education, there is an exodus of qualified teachers; wouldn’t it be logical to predict similar behavior for individual Practitioners?

Only 1/3 of practitioners participating in Medicare B are subject to MIPS participation – how can anything go wrong?

Related Post: MIPS Eligibility Letters: You’ve Got Mail. Now What?

While writing this post, two additional items appeared in the email in-box:

- 2 in 3 Medicare clinicians exempt from MIPS – This bulletin appeared in Becker’s Hospital Review on May 12th. The author didn’t cite her source material, but stated that CMS data showed physician practices were notified that only 418,849 Clinicians were required to participate in MIPS, while 806,979 were exempt.

- Jim Tate, the country’s leading EHR Certification Consultant, is an expert at deconstructing CMS regulations. He believes that many practices will benefit economically from MIPS participation. His recent article on MIPS reporting encouraged members of groups exempt from MIPS to consider voluntary participation.

For VBP reporting years 2015 & 2016, all medical groups of 2+ size were required to participate – many small groups failed to make the minimum effort, which is why CMS is exempting any ‘low volume’ practitioners for 2017. Jim’s article is a great idea – IF you are in a MIPS exempt medical practice that has VBP reports that showed high quality PQRS scores under VBP.

The current MIPS rules say that practitioners who are subject to MIPS (mandatory or voluntary) are compared to each other; half win, funded by the losses of the other half.

The Becker’s article indicates that 2/3rd of all groups are exempt; Jim encourages those that are exempt but capable of earning a high score jump back in the ring. What does that mean for LTPAC groups that have no option but to participate? I believe they face a very difficult task; in the absence of the CMS correcting their quality and cost risk adjustments for the LTPAC population – how are they going to fare in competition with medical specialties with favorable patient populations and bespoke quality measures?

LTPAC medical groups, and the institutions and populations they serve are stuck. Practitioners working with individual beneficiaries in these settings will personally inherit a MIPS score which will quickly equate to their market ‘value’.

Every medical work force study agrees – the country is facing an acute shortage of primary care practitioners, and a crisis in the field of Geriatrics. How will we retain and recruit practitioners when the payment deck is so stacked against them? How can the CMS allow these perverse policies to persist?